Lucie SCHNEIDER and Léo KACZOR

Facilitating and organizing collaboration between heterogeneous actors: a mirage of public policies or a new way of making the city?

Collaboration between different actors in making the city is a modern phenomenon which responds to a democratic aspiration. However, it is a true challenge for the different stakeholders of a project, even harder to overcome if the actors are not used to collaborate with each other. Yet several projects with different approaches try to encourage this collaboration and to allow the creation of new social links. If collaboration during the design of the project is effective, it is often more difficult to value its benefits. Finally, such projects face real barriers, which are not easy to overcome.

“The way we design a city is the way we are going to live in it. ».

These words from Lille’s Mayor Martine Aubry, when Lille was selected as 2020 World Design Capital, illustrate the importance of the design step of the projects, which is decisive in the use that will be made of them. In this context, collaboration becomes a central and essential element in the city’s design and public policies.

Collaboration as means of building

the city of tomorrow

To collaborate or cooperate means to implement a process of co-construction of knowledge that goes beyond the traditional oppositions between practical and theoretical knowledge, the knowledge of the user and that of the expert. These knowledges are different and complementary. The goal is to create a space where everyone can participate and build a project together. In this case we talk about horizontal organisation. Ideally, collaboration would take place in all steps of the project, and each stakeholder would be on equal terms (communities, planners, civil society…).

Traditionally, decision-makers make the city and public services without involving the local population. In her article “La recherche sur les acteurs de la fabrication de la ville: coulisses et dévoilements” published in 2019[1], Véronique Biau explains that the turn of the 2000s leads to questioning the “top-down” model in favour of a collaborative dynamic in which citizens are invited to intervene.

However, stakeholders are used to acting on their own, with their own techniques and languages. In practice, organising collaboration between stakeholders who are not used to working together can be complex. This difficulty in collaborating appears at several stages, in particular at the level of the project’s co-design, but also on the actual collaboration once the project is inaugurated. It is therefore necessary to question these difficulties, to study the factors involved, and to explore the solutions that are implemented in order to overcome these obstacles, while analysing their range.

[1]Territoire en mouvement, Revue de Géographie et Aménagement 2019

Trait d’Union project: the cultural and social city of Armentières

Following the initiative of the town hall, the former Middle school of Armentières (a town in the European Metropolis of Lille) has been rehabilitated as a Social and Cultural Centre to house municipal services and associations. This project is carried out in collaboration with designers whose work consists in bringing different audiences together. For example, the former courtyard is being transformed into a shared reception area and is intended to become a place for living and meeting people. The regrouping of the various municipal services and associations in the same place will encourage new collaborations.

Collaboration between heterogeneous actors in the

co-design of projects: a necessity in order to obtain

a service made for and by users

According to the digital think tank “sustainable network”, citizens are the first beneficiaries of urban development and for this reason they are in the best position to think and develop projects that make the city pleasant and attractive. According to this logic, in order for the city to be smart, civil society must be an actor in its development. For this reason, one of the challenges is to make inhabitants understand the issues of collaborative approaches so that they can participate in the project. This participation can be achieved through public consultations. For example, as part of the Social and Cultural Pole of Armentières project (see the box), the designers interviewed various organisations and associations that will occupy the site to determine their needs, constraints and work habits, but also the service users to find out their expectations. By consulting the various organisations that will occupy the space it is possible to build a place that meets their expectations.

Furthermore, listening to users enables to develop a service that better matches their needs, and is the first step in setting up an easily appropriated public space. However, it is possible to go further in the collaboration by directly involving users in the design of the project, as is the case for the Roubaix Station Car Park (see the box): the design team went to meet the city’s inhabitants in order to collect their testimonies about the places surrounding Roubaix.

The aim of these testimonials is to associate places of life with emotions, in order to create an “emotional journey” in the heart of the city. These life stories will then be transcribed in the car park in a graphic and sound way. This approach is rather new and has been a success: the residents of Roubaix have invested themselves together in the project and can appropriate the place.

To facilitate the emergence of ideas, Alain Renk, an urban architect, has developed “Cities without limits”: an augmented reality device that allows everyone, from a digital tablet, to imagine realistic transformations for a neighbourhood. The user is not asked to validate a project that has been presented to him or her, but can propose his or her own project. In this way, everyone can submit their own ideas and enrich those of others, whether they are professionals or not. The roles are less fixed. Several cities have already tested this system for specific operations, such as Montpellier, in the south of France, where the inhabitants have appropriated the tool and then organised co-design workshops, even involving a local school.

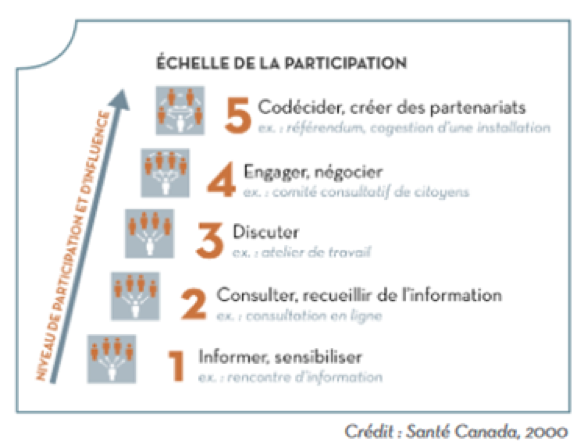

Yet, these projects fall relatively low on the scale of participation carried out by the Centre of Urban Ecology of Montreal, which defines five levels of participation and influence.

These projects are at level two, “consulting people and gathering information”. This is not a collaboration of equals: the collaboration is fully organised by the project leaders and citizens are not involved in the final decision making. One could imagine a more egalitarian collaboration with a citizens’ initiative and then a joint management where everyone would have a role to play.

Roubaix Station Car Park Project: Co-design of an emotional journey.

In this project, currently taking place in Roubaix, city of the European Metropolis of Lille, the designers invited the inhabitants to associate emotions to their living places. These emotions will then be taken up in the four levels of the station car park, and represented graphically and acoustically. The aim is to allow residents of Roubaix to tell their city to car park users who do not live in the city, in order to encourage them to come and visit the city of Roubaix.

Credit : Collectif Graphites

Collaboration to recreate social interactions

Co-constructed projects are better accepted by citizens and promote the meeting of heterogeneous people. At the Armentières Social and Cultural Centre, the courtyard has been converted into a shared reception room: all people using the various services and associations will all arrive through this entrance, where they can drink a coffee, read a book, children can play… The designers imagined this space as a feel-good area, a place to live and to meet people. Thus the Social and Cultural pole aspires to recreate social links between people who do not usually meet each other, as for example between the public of the music school and the public of the « Resto du Cœur » (charity association).

At the Car Park Station in Roubaix, the murals and soundtracks composed of testimonials from Roubaix residents triggers curiosity of car park users, who often are not from Roubaix and do not necessarily know this city. Through these testimonials, whether visual or

auditory, users may perhaps want to take the time to walk around Roubaix, and maybe meet the inhabitants. Therefore this device creates an indirect link between visitors and the inhabitants of Roubaix.

In these approaches, design is a real asset in order to foster social ties. As the sociologist Benjamin Pradel said at the International Design Biennial in Saint-Etienne (France) in 2019, “Design as a creative activity is as many signs and holds that will open or close, create conflict or social ties for individuals who will appropriate the city”[1].

[1]Le design urbain, créateur de lien social”, lyoncitydemain.com

Collaboration between very different actors

faces many obstacles

The collaboration of different stakeholders in the development of public policy or urban planning is a relatively recent phenomenon, and therefore the culture of collaboration is not yet rooted among the different actors, which makes a first challenge. In Armentières, municipal officials had to be convinced that working with designers brings real added value to the project, even if it changes some of their practices and habits. In an unusual collaboration such as this one, actors may show reluctance. This limit can be overcome by different means, for example in the project « Villages of Future » (in Burgundy Region), the first step of the collaboration was to train regional agents in the practices of co-design and collaborative creation.

Then comes the question of the sustainability of the collaboration. So that this collaboration is not just punctual, it is necessary to accompany the movement, to support it and to make it live on the long term. It is the case at the Cultural and Social Pole of Armentières, where the pilots of the project plan in a second time to

use design to favour the emergence of transversal projects between the various services and associations which occupy the place.

In the Roubaix Car Park Station project, collecting the inhabitants’ testimonies was another difficulty. Indeed it is necessary to be able to define the number of responses desired, to establish the different profiles to be interviewed, so that the work is neither too narrow nor too broad. Besides it is necessary to be able to establish a natural discussion with the inhabitants, in order to catch their real feelings without filtering, and thus to be able to use these testimonies without distorting them.

Finally, when a project it is still in progress, it is difficult to see all the scope and possible implications, there is not yet sufficient hindsight to be able to assess the sustainability of these collaborations, nor to be able to evaluate the effectiveness of the implementation of these projects.

Conclusion

The collaboration of different stakeholders in urban planning or public service design is a relatively recent process which is not self-evident. None of the stakeholders are used to it and this can lead to difficulties, either in the implementation of the project or in its use once it is finished. However, these collaborative processes deserve to be developed, particularly with citizens because their participation enables to create a product or service that corresponds to their needs and uses and because by participating in these projects they can appropriate them.

Moreover, a co-constructed place is more likely to generate interaction and dialogue, and thus social bonding. Yet, in this kind of project it is necessary to ensure the most heterogeneous inclusion of citizens, otherwise it would not be truly collaborative. Finally, it is difficult to draw conclusions on unfinished projects: will the results meet expectations? Will these projects really bring about contact between users in the long term?