Andréa Dague and Diane Darbon

Space development in the service of co-production

Third places that meet new needs in office real estate for more flexibility, for the benefit of freelancers, multi-tenants or new users.

Co-producing together and animating emulation between the users of third places.

In June 2017 the European metropolis of Lille launched a “call for permanent third-places projects”in order to set up creative and contributory mechanisms in Lille. The applications include projects for workshops and shared workspaces. These co-working spaces bring together self-employed workers who pool specific resources linked to a typology of profession. For professionals, it’s about proposing their idea to reinvest the space and include other users in the project.

A third place is the intermediate space between work and home.

What is a third place?

The concept of Third Place comes from the American sociologist Ray Oldenburg. Something he calls hybrid places, being neither home nor work, and neither public nor private spaces. The goal is to be able to exchange in informal ways. These spaces are different depending on the actor carrying out the project. In the framework of Lille World Design Capital, it is the European metropolis of Lille that frames different projects and brings together its own forms of collaboration. What interests us is the way in which the workspace can be organised to create new forms of contact and bring together the users of a same place. To do this, we studied the adequacy between animations and the temporary relocation of people and workspaces thanks to innovative and flexible furniture.

Third place and space development

Third places deal with multiple realities. Public policy defends the idea of urban planning being no longer the sole and exclusive role of experts, but being one that allows for collaboration between heterogeneous users and empowerment of these users once the project is completed. Third places are the new challenge in the making of contemporary cities. It will then be a question of asking how the actor-users are brought to invest and acquire a third place? To what extent could a multipurpose third place with malleable furniture allow people who, a priori, have diverse and even incompatible needs and uses, to be together? We therefore studied the central role that furniture, designed for and by users, can have within a third place, to encourage “co-production” and how the layout of space modifies usual workplace interactions.

How to induce collaboration and what role do third places hold within

this process?

Time has come to work together in cities and neighbourhoods, to encourage people to work together. But why is this approach becoming a such a goal for attractive territories that wish to become part of a new reality? According to Jane Jacobs (The death and life of great American cities), collaboration disappeared from our cities because cities experienced a specialisation of their territories. In other words, people with same interests, journeys and ambitions were brought together in the same places. Most striking examples include the Silicon Valley or large universities campuses such as the Saclay Plateau in France. These territorial specialisations stayed amongst themselves and thus reduced the possibilities of collaboration with other specialisations.

The collaborative incentive movement tries to undo this by bringing together people who are not usually brought together because of, among of other things, their spatial segregation often leading to social segregation. In the encounter between these populations who usually never meet, third places represent a great opportunity to bring them together. Indeed, third places offer a space for meeting and pooling by the simple act of proposing a place dedicated for this aim. Ray Oldenburg, American urban sociology professor and author of book The great good place, key for this subject, presents third places as inherent to the construction of a sense of community and common sense in a small territory.

What place for design?

According to the 29th General Assembly led by the “Professional Practice Committee” within the “Word Design Organisation”, design “is a problem-solving methodology that drives innovation, builds business success, leading to improved quality of life.” Design is embedded in purely material sectors of activity but concerns also other sectors such as economics, social, public and local policies. Design is a tool that allows linking pre-existing devices or entities to new innovations. The finality that these innovations represent comes to be at the end of a process that aims to put human beings at the centre of the discussion. Analyses and field surveys are carried out, as well as interviews with users. Generally, and even more with co-production, future users are invited and thus take part in the conception of new innovations.

To verify the application of the setting up of third places, Lille Word Design Capital coaches the driving actors of the projects. How are collaborative city and third places framed into new spatial planning considerations?

What is St So Bazaar?

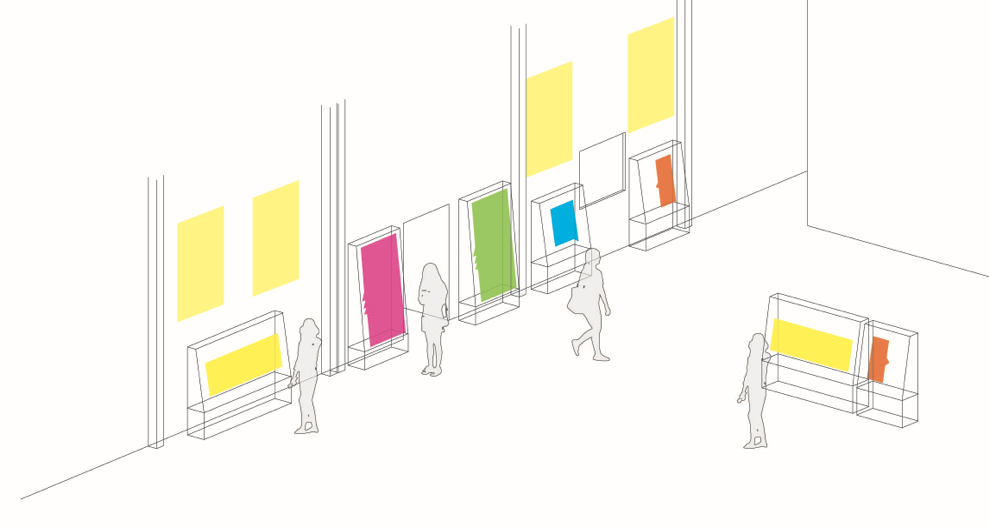

It is a reinvestigation project of St Sauveur station’s industrial wasteland. The city of Lille has chosen to turn these 5 000 m2 into a third place, a place for meeting and innovation between populations that do not usually meet. St So Bazaar will have a space reserved for professionals under a lease system, a free co-working space as well as a cafeteria and an exhibition area.

Kappla mobilier c’est quoi ?

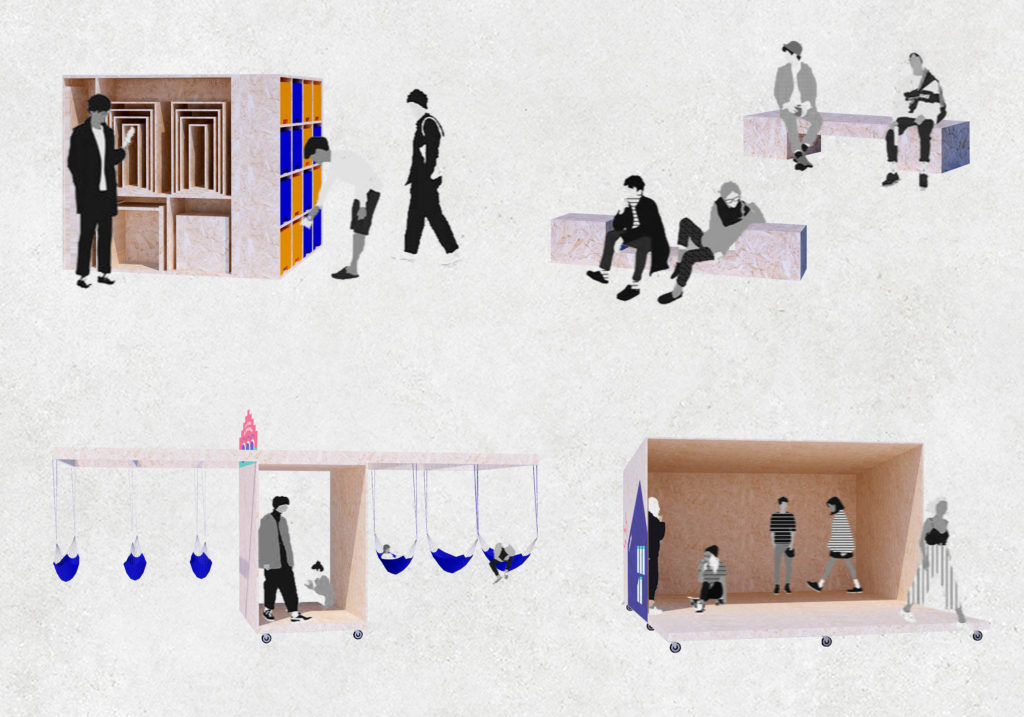

Kappla Mobilier is a project developed by two designers following a call for proposals « Tremplin Design »as part of the nomination of Lille Metropole 2020, World Design Capital. The two designers imagined malleable and flexible furniture that can be transformed according to the user’s needs. The name is a reference to the wooden construction set. For example, one light imagine blocks on wheels, benches that can be transformed into walls if necessary.

It’s the designers’ wish that these transformable pieces of furniture are imagined in collaboration with future users. To do this, they organise workshops in small groups for best exchange of ideas.

There are two important dimensions within third places; “co-location” and “co-construction”. For Oldenburg, third places are affected by two flows: the social flow and the cognitive flow. Social flow relates to the success in bringing together people from different backgrounds who do not normally meet. Cognitive flow, on the other hand, is the ability these actors acquire to think and create together.

This dimension is made available in particular through the provision of tools that encourage creation. Kappla Mobilier, by proposing malleable and flexible furniture, anchors itself in this perspective. The two designers at the origin of this project imagined furniture to fit out a space so that it matches each user, something designed for them but also with them. On previous projects, the two designers already achieved this type of collaboration through participatory workshops and “story telling” techniques. Story telling allows participants to tell their stories as fragments of lives. Throughout this process, the designers compare all the stories and bring out similarities, as expectations and common needs.

Saint So Bazaar has taken over the Kappla Mobilier project in order to use the 5000 m2 of this disused station. In order to create a creative community between artisan and intellectual workers, it needs to have a vacant external structure and to split the space thanks to modules that can be moved around infinitely. The integration of Kappla Mobilier into the St So Bazaar project promotes cognitive flow and gives this meeting space another dimension. Beyond the collaboration with Kappla Mobilier, this innovation will allow professionals to use the space for work and to stimulate creativity. In addition, there will also be spaces open to the public like a cafeteria, a daytime co-working space or living areas that allow for greater diversity and understanding between different actors. Diversity and renewal are at the heart third places, to broaden the spectrum of possibilities.

This approach makes it possible to develop spaces in perpetual redevelopment, which differ from traditional structures and arrangements which, once installed, are very difficult to modify.

The challenges that still need to be done

- A long-lasting community

In order to succeed in making a community come alive, users must invest in the space in a sustainable way. This investment starts at the time of the third place’s design, and all along its development, but extends also to relations and exchanges that last over time. As far as investment in design is concerned, it is sometimes complicated to mobilise future users, particularly in design workshops, since a feeling of illegitimacy prevails. Future users might think special skills are needed to participate, which might block them. To perpetuate the exchanges, common spaces such as those present in St So Bazaar, as well as exhibition spaces, can be great vectors of convergence and socialisation.

- Inspiring the city

Slowly, coworking is making its way into urban planning, with a direct impact on its organisation. Saint So Bazaar is a good example of vacant public space appropriation. In order to reach its full potential, the project must take part in the territory, adapt itself to local issues and have a stimulating vision. However, there are limits to this perspective. In order to inspire and influence the spread of collaboration at the scale of a city, it is necessary to succeed in reaching out to all professionals. But before selecting and validating profiles, these same profiles have already been pre-selected, which damages the integration process. This limit is difficult to exceed since there are few available places, yet, removing the preselection would allow for more diversified profiles.

- Convincing companies

St So Bazaar interviewed members of a third place called LaGrappe in Gambetta in Lille. On this site, a high number of companies use these offices to work. St So Bazaar sought information from the workers on what they would like to add in their workspace. Accordingly, employees from LaGrappe are already planning to move to the future co-working spaces in St So Bazar. They know that they will find the adjustments they suggested beforehand. LaGrappe’s outreach is being exported to other parts of the city. This first initiative makes it possible to integrate a little more already viable and developed companies which are necessary for collaboration. For a collaboration to be effective and interesting it is important to have different structures in terms of size, nature and level of development.

What doesn’t work in the collaboration is also what makes it interesting.

You have to be able to get users, designers and large companies to interact at the start of projects. Public policy is interested in new issues willing to be more egalitarian and democratic. The goal is to involve users from all sides. We particularly focused on the workspace as a place for collaboration through the creation of third places. The importance of third places in urban planning must be pushed forward since it’s the future of working together, resulting in new projects and initiatives.

A new approach to co-creation overturns the hierarchies initially established. Usually we just say « we need a table, a chair » to the person in charge of the place who orders and sets them up. This new approach fits better to the atypical uses that can arise in places without standard furniture.

In a nutshell, the space layout of a third place is a way to update collaboration and design almost daily. Taking part in the co-construction process helps to give a sense of place. It is when the place is already built that users become designers who take ownership of their workspace.