Aymeric Jaillais, Lucas Crouzetet Cheverry and Theo Mannechez

Atypical partnerships, heterogeneous actors, ambitious initiatives or new conceptions of tomorrow’s society?

Today in France, 1,000 schools need to be renovated because of their age and obsolescence. This worrying figure raises questions about the ability of public actors to act alone for a sustainable renovation of public buildings. The role of the private actors can be to act by complement to address these deficiencies through collaboration between the public sector and the private sector. New heterogeneous actors, sometimes proving to be more original, are being added to these partnerships, such as associations, schools with their students and citizens, to name a few. It results in atypical partnerships.

Thus, for several years now, the State and the public sector in general have been collaborating alongside private players such as companies, associations and citizens’ collectives under public-private partnership contracts. These contracts can be of different nature, which generates a complexity caused in particular by the multitude of actors involved in the realisation of these projects. The two cases studied here, School Eco-Renovations and Silent Metamorphoses, are perfect examples of the multiplicity of heterogeneous actors that can act within the framework of public-private partnerships. The first concerns the renovation of schools in order to make them places conducive to sustainable development and ecological transition. This project is huge because more of 1,000 schools must be renovated within the next 10 years. The aim is to rethink the place of the institution represented by the school, in its social dimension and its territorial inclusion. The project is very ambitious because it is not a simple renovation that meets eco-responsible criteria, but rather a redefinition of what the school is and what it should be and its place in a territory. The second, concerns the protection of territories under the heading of environmental protection, particularly in the northern territories of France.

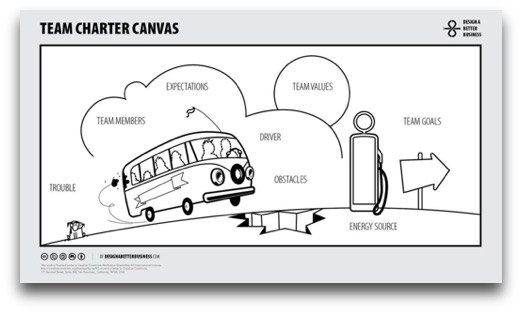

The two projects studied have the particularity of mobilising many actors, creating complex partnerships. These POC offer us an atypical example of partnership, differing from the simple traditional contract between private and public actors. The whole of civil society is now interested in participating in various projects, and the government is increasingly working with it in atypical partnerships. But it is also perhaps here where the main difficulties of these partnerships come into play: how to make actors with different origins and motivations collaborate and work towards a common final goal?Can we make actors from different horizons work together to obtain results and thus legitimise the action of private actors? These questions, which we are legitimately entitled to ask ourselves, are the stakes and the success of these partnerships.

In the public arena, partnership has become the watchword of public policy institutions and actors. The idea of partnership is to bring together the skills, resources and efforts of different actors to try to achieve a societal project in the most effective and efficient way possible, but also to seek to achieve it in a new way, under a more original approach and prism. While there is a notion of association in the partnership, it is not just thought out based on communities. Indeed, the partnership is also, and above all, conceived because of existing differences, giving rise to a paradoxical, interactive and evolving partnership relationship. In 1993, Zay and Gonnin-Bolo defined the partnership as the “minimum joint action negotiated” in the colloquium on “Establishments and partnerships” held at the NPRI. This definition makes it possible to distinguish between, on one hand, the notion of “subcontracting” and “delegation”, which are not subject to negotiation, and, on the other hand, “sponsorship”, which marks the financial, and simply financial, commitment of one player to another for the purpose of enhancing the value of his brand. It is then possible to pose the partnership as an action between two or more organisations aiming to solve a common problem from the differences of each one and in a search of complementarity.

It emerges from this definition that the partnership is the expression of an ideology, that of the end of the hierarchical model in favour of a contractual model. In addition to being an instrument of organisation, it has become an end in itself, a value of cooperation and pooling aimed at resolving a societal issue. For this reason, original partnerships generate the creation of collaborations between heterogeneous actors with different concerns or visions on the theme but who manage to agree on the same project.

The Silent Metamorphoses project relied on design students to draw the contours of a project, aiming to be adaptable to the requirements of each field and each population concerned. The relationship, far from being hierarchical, is a fair collaboration between a laboratory seeking special expertise in a specific field and students who take the opportunity to enrich their experience by putting their theoretical knowledge into practice. The Eco-Renovation of Schools project is at the heart of an immense collaboration between more than 110 actors of various and varied natures, ranging from private companies to public administration, as well as elected officials and citizens wishing to get involved. At the very foundation of these collaborations between a multitude of actors, heterogeneous in their origins, ambitions and natures, is the mutual willingness to exchange theoretical knowledge and practical know-how. This has led to ambitious projects, such as these case studies, which serve the global ambition of a societal ideal. Within the framework of the Maison Ville Collaborative, they fit, by their motivations and objectives, into the framework of this project carrying a new and original vision of tomorrow’s society.

The heterogeneity of the actors constitutes in itself a challenge in the co-construction of the project. In its purely conceptual realisation, the challenge is to get novices and experts, designers and students, for example, to work together. The ambition to involve citizens in the definition of the concepts, while offering the possibility of taking into account precisely the needs of the main stakeholders, implies delimiting the scope of their participation. The co-definition and implementation of projects by heterogeneous actors then takes place over a longer period of time. The implementation of projects on a scale such as the eco-renovation of schools implies the participation of various actors (public and private) but also requires the mobilisation of various sources of funding. As in any project, this is a central issue that can be a major obstacle to the implementation of these projects. In such cases, public-private partnerships are an interesting solution as they make it possible to compensate the lack of public funding with private funding from companies interested in the methods used in the design of the work in question. Some projects may involve a never-ending search for funding, leading to the addition of new actors to the projects. Beyond the simple question of funding, the motivated commitment of various actors with sometimes divergent interests and aims produces ambivalence by multiplying and optimising the manpower associated with project implementation while at the same time increasing the complexity of the organisational burdens. These partnerships complicate project governance at different levels: project steering, responsibilities (even imputability), regulation, transparency.

In short, the partnership can be presented under various aspects. It is a question of bringing together very different experiences and know-how. The partnerships presented here are also an opportunity to redefine the roles of each one. Citizens can have a central role in the development of projects. Theyare, after all, the first ones concerned by the eco-renovation of their children’s school. The student brings a fresh perspective and creativity that, combined with the experience of a veteran designer, can lead to truly innovative and sustainable projects. The development of this aggregate of skills requires of course a great deal of coordination as well as a real willingness to take everyone’s opinions into account. These experiments, because of the difficulties (particularly financial) they encounter, but also because of their desire to involve heterogeneous actors, appear to be innovative solutions to the difficulties faced by public actors in proposing solutions to complex problems (which by their very nature require collective responses). This type of partnership appears to be a promising solution for the future, at local, national and transnational levels.